Location: Saigon, Vietnam

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam was born of war and bloodshed. And like patriots in the United States of America, the Vietnamese describe the creation of their nation as a people’s victory over colonialism and freedom from invading, foreign forces. But compared to America, the modern-day government structure of Vietnam is very young; its revolution isn’t even half a century old.

I arrived in Vietnam the same month that celebrated the 40th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War (also known by locals as the Resistance War Against America). There was a huge parade in Saigon to commemorate the Communist victory and the creation of Vietnam’s modern government structure. Soldiers and students marched through the crowded streets carrying images of Ho Chi Minh, a past prime minister and revolutionary leader of the Viet Cong during the war, and singing the national anthem. The first verse of the song, which I heard several times playing in the background of public areas and national monuments, remembers the war efforts:

Soldiers of Vietnam, we go forward,

With the one will to save our Fatherland

Our hurried steps are sounding on the long and arduous road

Our flag, red with the blood of victory, bears the spirit of our country

The distant rumbling of the guns mingles with our marching song.

The path to glory passes over the bodies of our foes.

Overcoming all hardships, together we build our resistance bases.

As an American, the violence of the song is particularly cringe-worthy. I know that when the Vietnamese people cheer and cry out “the path to glory passes over the bodies of our foes,” they’re probably referencing American soldiers killed in action during the war. And beyond the question of whether America’s involvement was wrong, the idea that school children are celebrating the death of your people is bone-chilling.

Though I’d heard the song before, it was always in Vietnamese so it wasn’t until Da Lat that I realized the nature of the lyrics. I was hanging out in the lobby of a hostel with several friends, a few other travelers, the owner, Mama, and her daughter. One of the British guys I’d been traveling with made a crack about my people’s undying devotion to freedom and bald eagles. Someone else began to hum the Star-Spangled Banner and suddenly everyone in the room joined in, including Mama. Afterwards, people began to laugh and say where they knew the anthem from, whether it be boxing matches on television or Hollywood films. The two Brits had no idea how the English anthem started and a Swedish guy could only hum the first verse of his country’s song.

“What’s the Vietnamese national anthem, anyway?” Someone asked.

“Oh, you’ve definitely heard it before. They play it all the time. That and the ‘Ho Chi Minh’ song.”

A traveler played it off his tablet. Mama, who had been standing over us all, trying to get everyone to take second helpings of the potato-rice-chicken concoction she’d just cooked, clapped her hands together in excitement when she recognized it. She snapped up straight and pretended to march, loudly chanting the first few lines. Then, in a single motion and without missing a beat, Mama suddenly dropped her plump self to a low squat, pretended to cock a rifle in her arms, and barrel rolled across the floor, ducking between two chairs. She then army crawled forward and pointed her imaginary gun at me, still singing. And as the line ended and before the next began, she pursed her lips together and belted out a string of shooting noises.

Everyone laughed, including me. Mostly out of shock.

As the song continued, Mama leapt across the room, dodging invisible bullets and finding hiding spots that gave her better angles to aim at me. And the whole time she continued to serenade us in the Vietnamese lyrics that I now know:

Ceaselessly for the people's cause we struggle,

Hastening to the battlefield!

Forward! All together advancing!

Our Vietnam is strong eternal.

At the beginning of my stay in Vietnam, I discussed the nature of propaganda in my post about the Hoa Lo Prison Museum. But in light of my experiences over the past month and a half, I can’t help dwelling more on the subject, this time from a different angle. The question that keeps twisting about in my head is less about the Vietnamese youth of today and what they’ve been taught in school about the past, and more about what the Vietnamese that lived through the war remember, men and women like Mama, who were adolescents and young adults when it all took place. When I think of the struggles of the same American generation, I think about the Civil Rights Movement and how the violence that occurred during that revolution and the ingrained bigotry of the previous generation still affect the USA, today. Of how we’re still working to move past stereotypes and fight for equality.

The Vietnam War was so violent, so full of human rights violations, terror, and anger, that I can’t imagine people have completely put their experiences with America’s tanks, guns, and bombs behind them.

One of the most famous, gripping images of the Vietnam War features a young, naked girl, the victim of a napalm bomb, running down a road, screaming and crying. It’s an example of one of the most protested aspects of the war: American use of these kinds of chemical weapons on civilian areas. Poisons like agent blue, agent orange, and napalm not only destroyed the people’s food supply and severely mutilated their bodies during the war, but also remained in the land. Today, the grandchildren of the Vietnam War generation are still suffering from these chemicals.

The residual effects of agent orange are particularly prominent. Since the end of the war, the Vietnamese Red Cross has registered over one million people as disabled by the chemical. The common effects include physical birth defects like extra or mutated limbs as well as mental disabilities like Down Syndrome. When I first arrived in Hanoi, I saw a man whose legs were so deformed he was forced to waddle down the street in a squatting position. I wondered if he was a victim.

In Saigon, I met a man whose face was scarred by napalm burns. He’d been lounging on his motorbike when I walked past. His relaxed-but-poised position made me smile and I asked if I could take a photograph of him. He said ‘yes’ and afterwards, hopped off his bike.

“Where are you from?” He asked.

“America.”

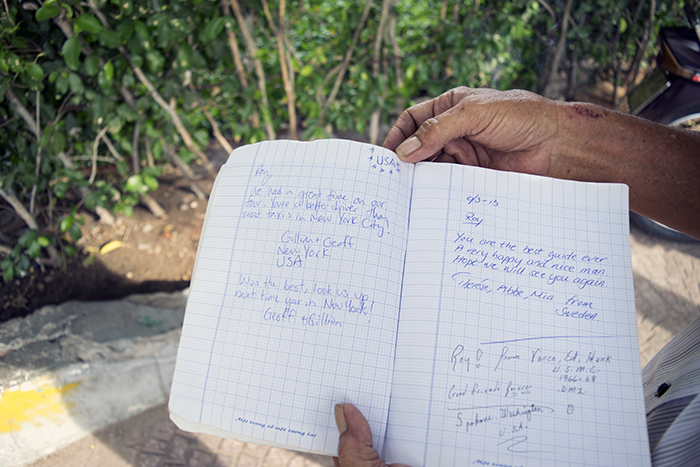

“Yes, America. I was in the war.” He pointed at the discoloring sprinkled across on his nose and cheeks. “From the war.” He told me he now worked as a tour guide in Saigon. He pulled out a notebook filled with reviews that other travelers had written about him. There were several pictures of happy families standing with him.

“Americans!” He pointed. “I like Americans.”

All of Vietnam’s museums and monuments dedicated to the war describe the “great victory” over America. They celebrate hundreds of national heroes, men and women that fought bravely against their foes, whether by building roads or by shooting down soldiers. The words “hope,” “strength,” and “communist spirit” are common. And I wonder if Americans would be so accepted here if the war wasn’t seen as such a triumph for the Vietnamese people.

The day after I met the man with the burnt face, I visited the War Remnants Museum. It’s a popular tourist destination in Saigon. Travelers sometimes compare it to visiting the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC, describing it as a “depressing” but “necessary” experience. Others told me that I didn’t need to visit both Hoa Lo and War Remnants; they are both just examples of propaganda in Vietnamese culture. But my inner-nerd was craving some history lessons and culture shock and I made sure that I saw them both.

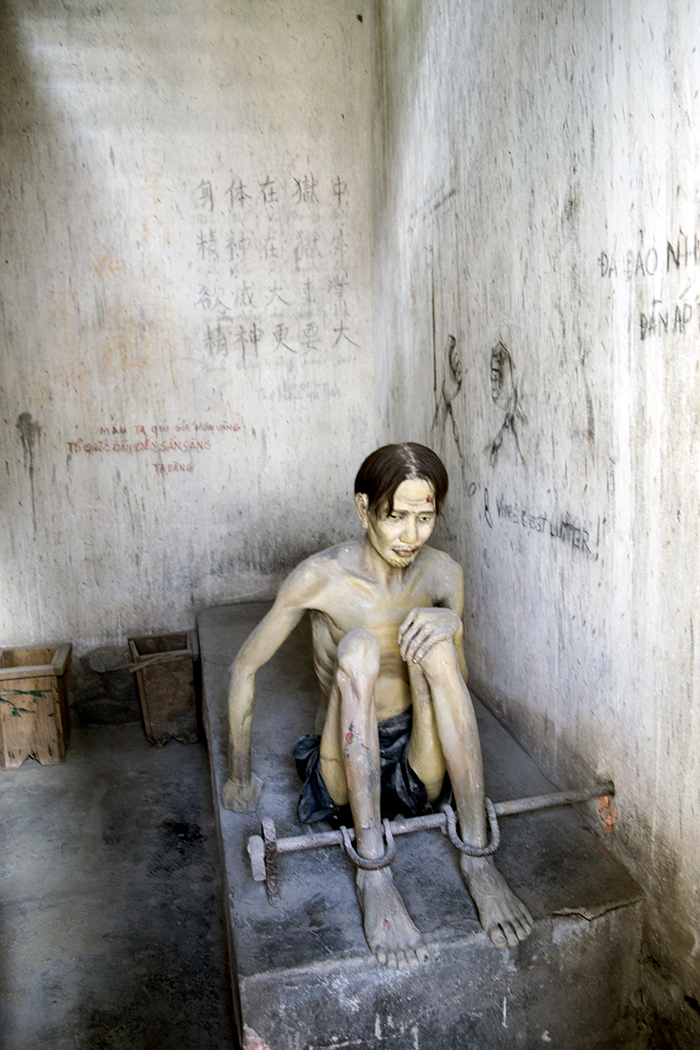

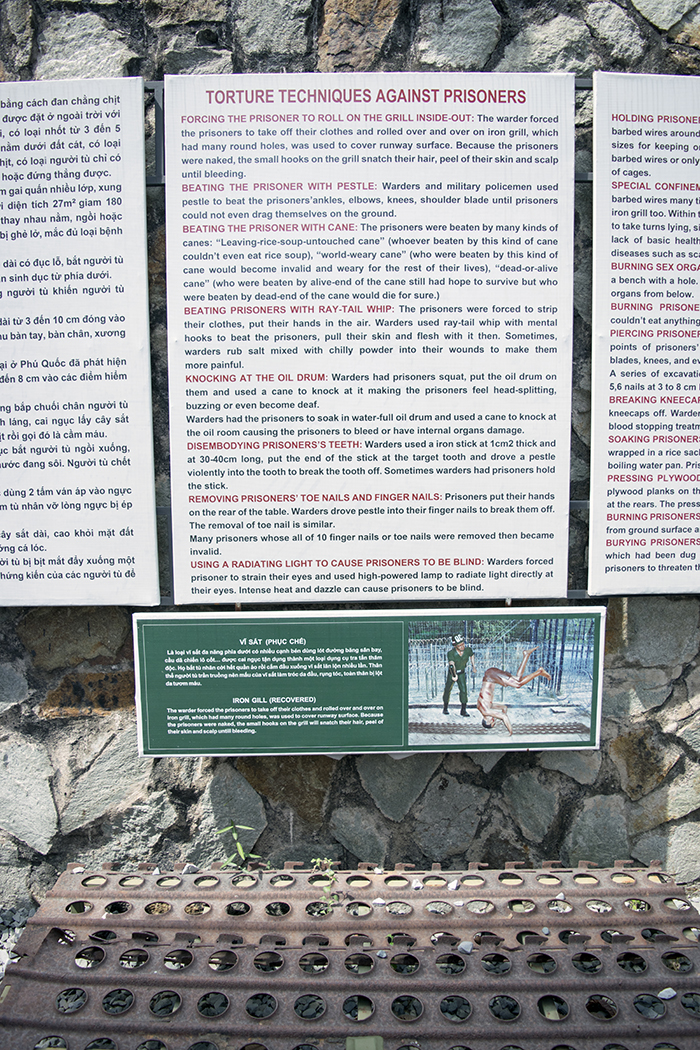

Instead of a sculpture garden, the front lawn of the War Remnants Museum displays all kinds of US killing machines. There are armored tanks, small fighter planes, and helicopters displaying machine guns. It’s actually pretty cool. You’re free to wander around and even touch most of the artifacts, whose rusty, chipping exteriors are warm from the afternoon sun. Behind artillery is an area devoted to torture equipment used in the days of French colonialism, just in case you momentarily forget about the wrongful treatment of Vietnamese prisoners back in the day. It holds similar contraptions to those exhibited in Hoa Lo. Metal cages, shackles, and barbed wire everywhere.

The inside of the museum is split between several floors. The ground level includes more weaponry; the bombs and shells Americans used against the Vietnamese. It also introduces the nature of civilian war casualties. Movie-poster-sized plaques graphically describe massacres of entire villages of people. It’s one after another of these; from the famous Mai Lai Massacre to smaller killings of families, grandparents, toddlers. There are clips from war journalists as well as from Vietnamese survivors. The walls are completely covered in graphic photographs. It’s almost impossible not to be totally consumed by the large-printed pictures of corpses stacked on each other, of children alive in one photograph and then dead in the next, of Vietnamese civilians screaming, their hands are tied behind their backs in “stress positions” as they’re dragged through the mud.

My stomach curdles when I notice that several images feature mutilated corpses wearing the traditional embroidered jackets and belts of the H’mong people, the ones who hosted me in SaPa. Mama Xung, who I spent so much time with, would have been a preteen during the war. Had she witnessed some of the violence? If so, she never mentioned it to me.

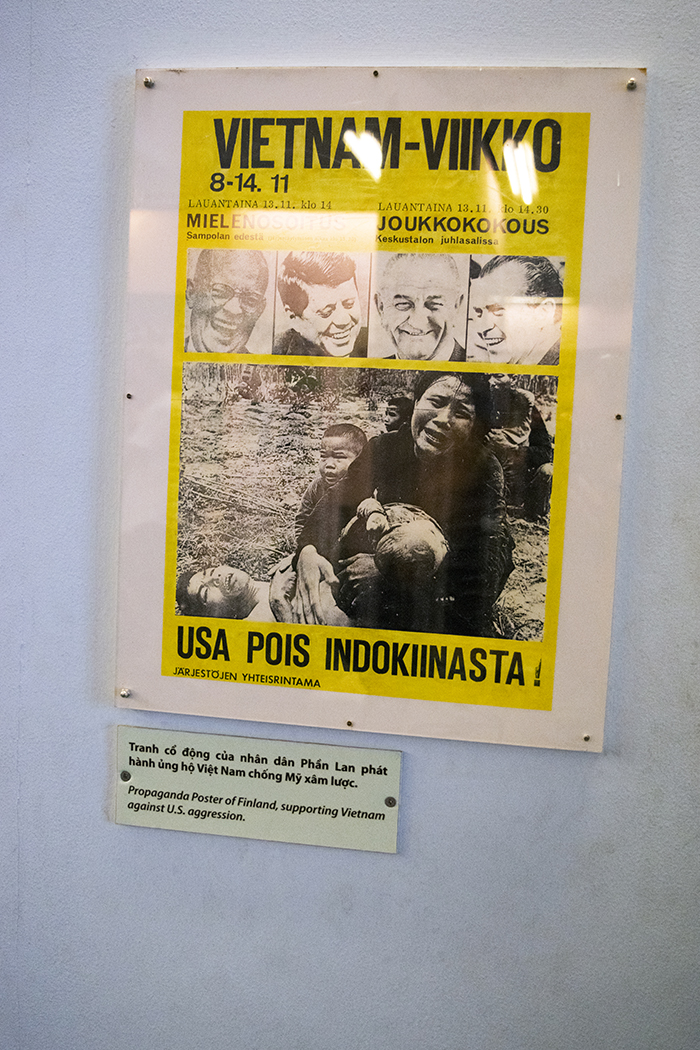

The next floor is devoted to colorful news articles, posters, and photographs of people worldwide protesting American involvement in Vietnam. As someone who didn’t witness the protests and who learned American history through the South Carolina public school system, it’s surprising to me to see how widespread the condemnation of American action in Vietnam was. I’m left wondering if that’s why we don’t emphasize it in our history books; is the residual shame too powerful to talk about, could it still test America’s faith in war and overseas democracy?

After that brief respite from the gore, you come to room filled from floor to ceiling with large, high resolution images of people disabled by agent orange. There are babies with deformed, cone-shaped heads, toddlers missing ears, eyes, and limbs, and women covered in flaking, red skin. Each is accompanied by a plaque with the victim’s name and a short description of their illness and life. Most end with a death date; barely anyone in the photographs has survived more than a decade of this painful existence. The worst are the sections with multiple images of whole families suffering from disabilities. One of my friends actually left this portion of the museum and sat in the hallway until the rest of us were finished; it’s intense.

Lastly comes the historical section. By the time you reach this area, if you’ve attempted to read most of the information in the rooms below, you’re already exhausted and overwhelmed. (I did, and it took me two hours just to reach the fourth exhibit.) And here it’s all numbers listing the casualties that have taken place throughout the war, both civilian and army-wise. It’s startling. The numbers covering the walls are just too many to read. Over 3,000,000 Vietnamese people died during the war. That’s like the entire country of Jamaica or the combined population of South Dakota, North Dakota, Alaska, and Wyoming. It doesn’t include the number of people permanently displaced or disabled.

I think about the fishermen in Cat Ba who still wear Vietnamese war helmets, the ones who brought me onto their boat and shared their moonshine with me. I think of all the locals who have given me directions when I’ve been lost, fed me when I’ve been hungry, smiled at me when I’ve walked past their homes, shared their lives with me.

Only 40 years ago, our countries were at war and my government authorized the systematic bombings of civilian areas, allowed entire villages of Vietnamese people to be wiped off the map, experimented with chemical agents that disfigured many innocent men, women, and children for life. Yet here I am, today, a visitor in the same lands that my government once condemned in the name of democracy, and the people of these lands are kind and generous to me.