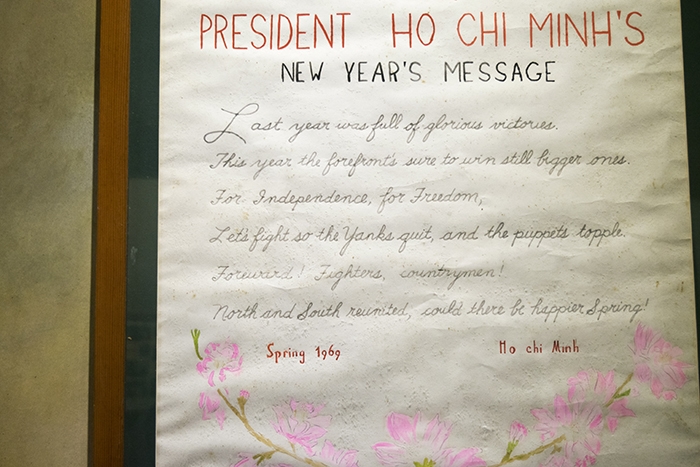

An artifact from Hoa Lo Prison Museum written and decorated by American POWs during the Vietnam War.

Location: Hanoi, Vietnam

We’ve all seen examples of blatant propaganda throughout history. A couple of the most famous ones that come to mind are the “I WANT YOU” Uncle Sam posters that the US government commissioned to recruit soldiers during World War I & II and “Reefer Madness,” a (now) cult-classic film first funded in the 1930’s by a church group hoping to scare kids away from using marijuana. Today, when we analyze the language used in these media messages, whether it be “drugs are bad” or “support your country,” it all seems obvious. And it’s hard not to look at examples of conspicuous propaganda and think that that kind of misinformation can’t possibly hold the same power in the age of Google. And I have to admit, that’s something that I, as an American and a millenial, have often taken for granted; that my liberty to access information is pretty much unlimited.

But that’s the thing about modern-day Internet censorship in communist countries like China, North Korea, Cuba, and Vietnam: misinformation can hold a lot more weight when you can’t fact-check it. And I encountered this culture shock not only in expected ways, like trying to access different stories on The New York Times or The New Yorker, but also in national monuments and places built specifically for informing the public about historic events, like the Hoa Lo Prison Museum.

A brief history: Hoa Lo Prison was first built by French colonists in the late 1800’s, back when Vietnam was still under European rule.1 They used it as a holding facility and execution center for Vietnamese prisoners, most of whom were charged with political crimes. The prisoners were shackled to wooden planks by their ankles in dank, smelly, overcrowded dungeons. Many were tortured in skin-crawling fashions; one of the most memorable was commonplace, a method in which several people were stuffed into coffin-like, barbed-wire cages in the prison’s courtyard and left to cook under the sun for hours.

Both men and women suffered in this haunting place. Heads were chopped off during executions and displayed in woven baskets to the prisoners. Many starved to death. And this was no temporary holding area. The prison remained open, it’s numbers growing from a few hundred to over two thousand, until 1954, when the French left Hanoi and Vietnam became the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.1 Several revolutionists, Vietnam’s kind of “founding fathers,” were kept in this prison for over a decade.

The prison was shut down from 1954-1964, when it was reopened during the Vietnam War (or the American Invasion of Vietnam, depending on your stance). It was here that the North Vietnamese Army held captured American prisoners of war (POWs) and interrogated them.

Now, this part might sound familiar if you’re a bit of a history buff. The Vietnam War was the first war the US entered where the on-the-ground violence was heavily photographed and videoed. This widespread media, one that documented the real horrors of the war for the first time, spurred controversy and anger from much of the general population and led to worldwide protests against US military involvement in Vietnam. But what you might not know is that the North Vietnamese army had its own plan to influence the general public. And that plan unfolded within the walls of Hoa Lo Prison.

The idea was simple: convince POWs, through whatever methods necessary, to speak against the US government and praise the North Vietnamese and their treatment at Hoa Lo. And “whatever methods necessary” quickly fell under the category of “cruel and unusual punishment,” also known as torture. It was in this place, one nicknamed the “Hanoi Hilton” by captured soldiers as an ironic reaction to the poor living conditions and abuse they suffered, that one of the most famous attempted-propaganda tapes from the Vietnam War was made. It’s a grainy, poorly cut film of a soldier speaking in queer stiltedness to the camera, answering questions during a press conference. And while he’s speaking, he blinks out “torture” in morse code.2

Back to the present: So here I am, meandering through Hoa Lo’s gatehouse, the only part of the prison left standing. There is, at best, an unsettling atmosphere within the yellow-painted, cracked walls. It’s the kind of feeling that’s to be expected when you’re in a place where you know many, many people have suffered, been tortured, and killed. And the museum has made that very obvious in the first buildings, which are dedicated to the horrific treatment of Vietnamese prisoners by the French.

There are life-size, wooden sculptures of prisoners in shackles; they all look half-starved, crippled, and there is an endless sadness painted onto their carved eyes. Some statues stare out windows while others speak with their bedmates. These figures have glass boxes of evidence beside them; old notebooks and copies of communist manuscripts that revolutionaries hid while imprisoned. All the plastic information plaques here describe the conditions as “horrible,” “inhumane,” and “unbearable,” and the prisoners as suffering but, because they believe in the spirit of communism, able to stay “resilient” and “strong.”

It’s true that the conditions were inhumane and though the language is obviously biased, I let it go. What could be the harm in people reminding themselves that their ancestors stayed strong even as they suffered? Who’s to say these men and women didn’t keep hope because of their strength of community?

Next, I enter the part of the museum dedicated to the Vietnam War. The exhibit is mostly images of POWs during their time in Hoa Lo. There’s a group of prisoners playing basketball here, another of men lined up for food there. One is a gritty, blown-up black-and-white photograph of John McCain (yes, that Senator and 2008 presidential candidate). It’s a famous photograph. McCain, then just a fighter pilot, was shot down during his tour in the Vietnam War. In the image, post-crash and capture, he is young- his hair hasn’t turned its signature snow white yet. He’s lying on a stretcher as a Vietnamese man in scrubs runs a stethoscope over his chest. His arm closest to the camera is taped up in a sling, his eyes are wide, his mouth is half-open, and he’s wearing an expression of excruciating pain and fear. He stares out of the frame at something or someone beyond the camera.

McCain has attested that when he was shot down, he fractured both his arms and one leg in the crash, then after he was dragged to shore by several North Vietnamese soldiers, they beat him with a rifle butt and slashed him with a bayonet. When he arrived at Hoa Lo, the prison staff refused to treat his injuries, instead interrogating him and assaulting him until they found out his father was a high ranking military officer. It’s reported that McCain lost fifty pounds during his first two months in Hanoi. This was only the beginning of several miserable years of capture for McCain, which included more torture and two years in solitary confinement. The injuries he sustained during this time left him permanently weakened.3

But the caption inscribed on the panel before me, the one hung so precisely below this image, describes the excellent treatment of American prisoners and how the North Vietnamese army used all resources at their disposal to make sure they were looked after. How all prisoners were regularly visited by doctors and kept in good health, including McCain.

I’ve been standing in front of this image for a long time and the museum is bursting with hundreds of visitors. It’s hot, crowded. The sun is shining down through the open windows on my back and I’m sweating in my tank top, but I’ve got goosebumps. A woman walks up to my left, spends just enough time to read the plaque and take in the photograph, then moves on without a second glance.

She knows these are all lies, right? I can’t be the only one here that’s shocked. Everyone knows that McCain almost died in captivity and that these are outright lies...right?

I panic. I have the briefest, wildest impulse to grab the woman’s shoulder as she walks away, to whirl her around and ask her. But it fades just as suddenly. I can’t just freak out on a random tourist over this piece of propaganda. What am I going to do if she doesn’t know what I’m talking about? Lecture her on the human rights violations committed by the Vietnamese during the war until I’m escorted out of the building by the museum’s security guards and (most likely) into a police car?

So I’m stuck. I move on to the next image, but a darkness has settled over me. I’d also visited the Women’s History Museum earlier in the week; there was a floor dedicated to the hundreds of thousands of women that were drafted into the war effort against America. I had previously never read about the importance of the infrastructure built by these women during the war and had been swept away by the images of brutal manual labor in front of me. I came across a section with images of particular female wartime heroes and their distinguished awards. One title that many drafted women soldiers held was the “Anti-American Hero Award.” It was an honor awarded to soldiers that killed many Americans.

No matter what your stance is on the Vietnam War, it’s sinister language. It’s no longer about supporting Vietnam or standing behind your country. It’s specifically rewarding those who kill Americans. It’s targeted. It’s something that would be considered bigoted and overwhelmingly negative in the United States. I can just imagine the protests over an “Anti-Vietnamese” hero award. Now, I know it’s not that simple. America hasn’t dealt with another country attacking its people on its land - not like Vietnam has. However, as an American citizen, I would heavily question, if not fully condemn, that kind of language. I also know that I feel that way because I have the right to, the ability to question my government’s choices. I don’t see that in Vietnam and I wonder how many people believe the propaganda that’s placed in educational institutions like national museums.

And it’s for this reason that I recommend visiting the Hoa Lo Prison Museum; it’s a cultural experience and total mindfuck, especially if you’re American. And it’s good to remind yourself sometimes of the freedoms often taken for granted.

1 Logan, William S. (2000). Hanoi: Biography of a City. University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 0-86840-443-8.pp. 67–68.

2 "Eyewitness". Archives.gov. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

3 Nowicki, Dan & Muller, Bill. "John McCain Report: Prisoner of War", The Arizona Republic (March 1, 2007). Retrieved November 10, 2007.